Kismet Takes a Hand

It Always Does Where There’s a Man and a Woman

With the sleeves of her blue linen smock rolled above her elbows, Patricia Langdon was intent on soldering a silver box cover. Slender, youthful, she stood with her foot on a treadle and by pressure increased or diminished the heat from the large blowpipe she held.

Her charming face was flushed, her beautiful eyes wrathful, as she turned to the man who perched on the end of her work bench.

“This is the second time within ten minutes that you’ve knocked Bruce Mackensie, Tony Brown. Now, why–“

“Why? Because you need enlightening. You’re too trustful. Mackensie takes you and Aunt Judith out to dinner, your aunt’s crazy about him, and where does he take you? Ever to the swell joints? Not a chance! Respectable Bohemia. What do you really know about him, Paddy Langdon? He blew in here six weeks ago and ordered a collar for a pet cat for his mother. Mother! Perhaps! Then he brought the cat. Now he comes every day to see how the collar is progressing and__”

“Not every day,” interrupted the girl coolly.

Patricia leaned forward, clasped her hands about her knee, and gazed speculatively at Brown’s lean, strong-featured face, at his inscrutable eyes, his flowing tie, his good but unpressed clothes. Even his slouching attitude bristled with intolerance and aggressiveness. But, to do him justice, he didn’t always slouch. He could be convincing and even lovable. Sometimes he almost swept her off her feet by his eloquence, almost made her believe that the biggest thing in life would be to work side by side with him. but why–why did he try to destroy her confidence in people?

“Tony, you are rather likeable in spite of your chronic grouch, or I wouldn’t listen to your advanced ideas on man. Now I will ask a question. What do I really know about you? Aunt Ju and I were hardly settled in these rooms when you ‘blew in.’ You have a lot of unfinished canvas standing about, but do you ever work? You harangue the slackers on street corners. Words, not deeds, seems to be your slogan. O, you’re a convincing advocate, all right: there are times when you have the original silver tongued orator beaten to a frazzle, but the trouble with you is that you have no toleration for the person who does not think as you do. That trait gives me pause when you have almost convinced me. You pose as a down-with-the-capitalist Socialist; you may be a dyed in the wool plutocrat for all I know.”

You won’t be annoyed with my tirades in future,” bitterly; “I’m going away.”

“Tony!”

“Yes. I’m through forever with the sort of thing I’ve been doing, and you’re responsible. Perhaps when I’ve made good I’ll come back, and then–” His eyes shifted from her startled ones. “What are you making?” with an abrupt change of tone.

Patricia was only too grateful to scurry away from thin ice, and answered gayly:

“A ring for Ginny, my cousin, Mrs. Johnston. Isn’t it a beauty? She wants it tonight, and I shall be pleased purple to get it out of the shop. I don’t like the responsibility of such a valuable jewel.”

Brown glanced at the stone, then at the open safe which stood against the wall directly across the room from where the girl sat at work. He could see the neatly folded white packets which contained precious and semi-precious stones. One compartment was stuffed full of greenbacks.

“Why do you keep so much money here?” he demanded.

In puckered brow intentness Patricia captured an elusive diamond from the glittering collection on the bench with her pincers before she answered:

“Because I have been too rushed with work to go to the bank. People have gone jewelry mad this year. Don’t glower, Antonio; I will deposit it as soon as I get time.”

“Get time! Isn’t that like a girl! A man would deserve to lose that money if he kept it where it was a temptation for some one to steal it.”

“Are you tempted?” dryly.

Brown colored darkly.

“I’ll bet a hat that you go off and leave that safe open.”

She leaned forward, eyes tantalizingly brilliant with laughter, and echoed melodramatically:

“I’ll bet a hat I do. It’s the artistic temperament, Tony. Now please stop your growling. I can’t work.” She dropped her tool in exasperation and lifted a silver collar from the bench.

“Here, Kitty! Come, Kitty!” she called.

A white Persian kitten with fluffy ruff and tail like a plume appeared in the doorway of the living room. He stretched lazily, yawned prodigiously, and jumped into the girl’s lap.

“When does Mackensie take his cat?” Brown asked curtly.

Patricia carefully adjusted the collar to the kitten’s neck.

“This afternoon.” With shining eyes she leaned back the better to admire her handiwork.

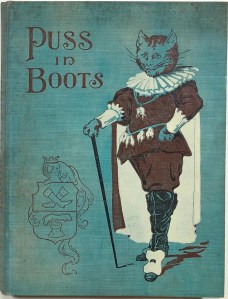

“This is the best thing I’ve done yet, Tony. The kitten’s name is Kismet. Those carved and tooled silver medallions between the links are scenes from the story of ‘Puss in Boots.’ Wasn’t the famous cat Fate to the master whom he made marquis of Carrabas? Those glowing cat’s eyes with their smoldering lights, which alternate with the panels are symbolic of health and a long life. The pendant from the buckle in front is apiece of Corean amber and is supposed to contain magic. That collar is a triumph. I’m not pleased with myself, am I?” in merry self-derision. “I just hope that Bruce Mackensie will be satisfied” with a quick change to gravity.

“O, he’ll like it all right. Trust him to make you think so, anyway. Are you going out with him tonight?” Brown demanded gruffly.

The girl flung down the tool she had just picked up.

“To be expressive, if not elegant, Tony, ‘Beat it!’ I must work. Your voice has taken on a subterranean tone which is far from stimulating, my gloomy friend. I am sorry that you are going away, but after all you’re going because you want to, aren’t you? I have this ring to finish and the kitten to send away before I make a mad dash for the 5 o’clock train. I am to meet Aunt Ju at the Johnston’s country place for the weekend. Now will you depart?” she asked half in fun, half in annoyed earnestness.

“I’m going, but first listen to a word of warning. You’ll have all sorts of men dangling about you. Take it from me, don’t marry a rich man.”

Patricia groaned.

“Again, Tony! You’re hipped on the subject of capitalists. Don’t worry! There may be some shreds and patches of my ideal of what a rich man might be still clinging to my mind after your insistent hacking at it, but take them and go, anything, so that I can go on with my work undisturbed.”

“Jeer if you want to, but one word more. Look out for Mackensie. He’s been deceiving you! I’ve found out that he–“

“Who’s been deceiving you, Miss Langdon?” called a gay voice as a man pushed the half open door wide and entered the room.

Brown’s face was livid with anger. His eyes and voice were vicious as he answered:

“You came just in time to hear, Mr. Bruce Mackensie–“

The newcomer wheeled upon him, but the girl hastily interposed. There was a suspicion of steel in her voice as she commanded:

“That will do, Tony. Go!”

With a muttered word Brown went out and closed the door behind him. Mackensie met Patricia’s glance steadily.

“With what bit of information was our friend about to stir the sluggish pools of my conscience? He’s rather given to the terrific, isn’t he?” he asked coolly, as he seated himself on the bench where Brown had sat a few minutes before.

From her stool Patricia compared Mackensie with the man who had preceded him. This figure was virile, wholesome, with a distinct trace of military distinction. The face was clean cut and fine, the gray eyes clear and compelling, the lips beneath the tiny mustache firm, yet boyishly tender. He seemed honest, frank, yet–Tony had unearthed something about him, something he had been about to tell her, and Tony__

Mackensie forced the girl’s eyes to his.

“How about it? Will I pass?” he queried. Patricia flushed daintily pink to the roots of her wavy, bronze hair. Her brown eyes darkened.

“Who are you?” she asked sternly.

He was on his feet ready for the fray in a moment, muscles of his jaw tightened.

“Who am I? A man who loves you. Wait a moment,” as she opened her lips to protest; “I have loved you from the day I came here to order the kitten’s collar, thinking that the P. Langdon who advertised as a metal craftsman was a man. You and that insufferable Brown, with his colossal egotism and his moss grown platitudes, have aired your views as to the shortcomings of men till I determined that you should love me for what I seemed to you, not for what you knew about me. You’re not only going to marry me, but you’re going to love me if–even if I have to kidnap you.” His tense voice broke into a boyish laugh.

Patricia felt as though a mighty wave had broken over her and left her gasping for breath. She rallied and smiled tormentingly.

“Oh-o, cave-man stuff! So you think you can make me love–marry you? You have another think coming. Tony Brown warned–“

“O, Brown be —-” he muttered under his breath. He moved until he leaned against the bench in front of her. “Brown has made you suspicious of every one. Now hear my creed. The majority of men have ideals about home and marriage. That is what I have learned from my contact with the world. I’m no saint as to disposition; in fact, I suspect that I may be rather a difficult old man, when my time comes, but, my word, I’m decent and I mean to be all my life.” He seized her hands and kissed them with a passion which sent her heart pounding to her throat.

“Don’t!” She wrenched her hands from his. “You forget that I don’t care for you in the least, the very least,” emphatically, though she avoided his eyes.

Mackensie gave his mustache a vicious tug.

“Doubtless you prefer your melancholy and temperamental friend Brown. You think that he’s a little bit of all right because he orates to the downtrodden and looks as though he had taken a Rip Van Winkle nap in his clothes,” he retorted angrily.

“You haven’t a real sunny temper, have you?” mocked Patricia, as she glanced over her shoulder at his angry eyes. “Poor little boy! Nobody loves him!” she teased. The kitten made a dash for the living room. The girl pursued him as far at the door, then turned. Mackensie was staring at her open safe.

“Now, don’t scold about that money, she anticipated, “I know that I am careless to keep it there, but–“

“How much?” interrupted Mackensie.

“Only three hundred.”

“Patricia, you’re made to keep it here–you alone–“

“Alone! When, now I ask you, when?” Exasperation crisped her voice. “What chance do I get to be alone? First Tony comes and harangues me, then you. I’d jolly well like the chance to be–“

“Don’t say it, don’t!” pleaded Mackensie laughingly. “Poor, pestered Paddy. Forgive me this time and I’ll promise to be good.”

He followed her into the big, old fashioned living room. A fire of cannel coal blazed in the grate beneath the carved white marble mantel. The bay window was filled with flowering plants. A canary trilled an ecstatic greeting from the golden cage. A large mahogany bookcase which had the staid, antique bearing of a made for the family piece of furniture, extended along one side of the room and loomed almost to the ceiling.

“Hand me Kismet’s basket, please,” commanded Patricia.

She stooped to pick up the kitten, but the kitten had views of his own. He sprang to the top of a high back chair, gathered himself, and with a bound landed on top of the bookcase. He peered down over the edge, his topaz eyes gleaming red like rubies. The girl stared back at him.

Chicago Tribune, Sunday, 27 April 1919

“Darn!” she explaimed with an ingenuousness which doubled Mackenzie up with laughter. “O, you think it’s funny! Quick! Get my umbrella and we’ll poke him down. The little imp. Do you suppose that that kitten knows you have come to take him and has decided that he won’t go?

The man, mounted precariously on the arm of a chair and poking vigorously at the top of the bookcase, paused long enough to reply dominantly:

“Kismet isn’t the only one who refuses to be banished. I’ll marry you if I have to wait the scriptural seven years and then some.”

At each thrust of the umbrella the kitten retreated. Mackensie cautiously moved his chair and renewed operations from that side only to have the kitten playfully scurry away. From the middle of his perch Kismet blinked complacently down on his tormentors. Particles of dust drooped from his long whiskers, dust adhered to his ruff, his body was a dreadnaught gray. At the imminent risk of breaking his neck, Mackensie lunged at the renegade. His chair tilted treacherously.

“O–O, do be careful!” warned Patricia. She dropped to the rug with a musical, irrepressible ripple of laughter. “I–I can’t help it! You–you looked so funny! Just like a windmill–gone–gone mad. Your arms–” Her words trailed off into a little peal of laughter.

“Patricia,” warned Mackensie sternly, “It is painfully evident that you are on the verge of hysterics. I know of only one sure remedy for that. I shall be obliged to kiss you. The cure will also serve as indemnity. You laughed at me.”

She was on her feet in an instant.

“‘Millions for defense, not one cent for tribute!'” she declaimed theatrically. She caught the glow in his eyes and compelled her voice to every day matter of factness. “It’s no use, the kitten won’t come down while you are here. It’s almost 4 o’clock now. I’ll scrub him and leave him in his basket with the janitor. You may come for him whenever you like.”

“But you are to take the 5 o’clock train for the Johnstons,” Mackensie protested.

“How did you know? I can take a later one. Aunt Ju took my suitcase with her. She’ll have my frock ready for me. I’ll phone Ginny that I shall be late.”

“Do you know about trains?”

“If I could just have a chance–” she suggested.

“I accept your delicate hint. I retreat,” he laughed. “I only hope that you will have as happy a week-end as I expect,” he observed mysteriously before he left the room.

The smile faded on Patricia’s lips, her eyes were darkly troubled as she looked unseeingly at the closed door of the shop. She locked it and returned to the living room. She glanced up at Kismet skied on the bookcase. The kitten seemed to grin at her triumphantly.

“Kismet, why did you take a hand in the game?” she asked wistfully, and she thought the kitten grinned a little wider. “Are you playing at Puss-in-Boots? If so, perhaps you’ll tell me if I ought to let myself love your master? He’s very compelling, but–but do you know what Tony was about to tell me?”

But the white kitten, bored already by the role of fate, only gave a drowsy “Meow!” in answer.

“Kitty, don’t go to sleep up there! I can never get you down,” pleaded the girl. She poured cream in a saucer and placed it on the hearth rug. With reckless energy she hurled a magazine at the aggrieved kitten. “That ought to wake you up!” she cried, and retreated to the shop. She listened. There was a soft thud. Kismet had descended.

With mind and fingers keeping pace, Patricia finished the ring, and with a sign of satisfaction laid it in the open safe while she put her bench in order. It was growing dark outside. The girl looked out at the street. The snow fell with noiseless, feathery daintiness. It sparkled on the trees under the electric light like tinsel on a picture postcard. The room was on the first floor and an old fashioned wrought iron railing inclosed [sic] a tiny balcony outside the window. the rialing looked like a bit of marble carving where its design was picked out with snow. Lights appeared in the houses across the park, and in a window the girl could see the shadows of dancing children cast upon the drawn white shade.

“A veritable fairyland,” she murmured as she turned away.

Her mood changed in a flash as she entered the living room. On the hearth sprawled the kitten, but such a kitten. The most debauched, belligerent habitué of a backyard fence couldn’t have been dirtier. Patricia seized her victim, removed the silver collar, and filled a tub. The kitten looked on in dusty, injured innocence. The thoroughness of the bath which followed was doubtless somewhat augmented by the turmoil of the girl’s thoughts. With the bunch of wet fur rolled in a blanket she dropped to the rug in front of the fire. She rubbed and brushed till Kismet was his fluffy, snowy self atain. She adjusted the silver collar, then leaned back against the chair to rest.

The room was dim and mysterious. The red coals of the fire flared and faded and blinked. Its light turned the white coat of the kitten to rose color as he stared unwinkingly at the flickering shadows on the hearth. The room was ghostly in its silence. The clock boomed the hour with a suddenness which startled the girl from her musing.

Five o’clock! If it hadn’t been for Kismet she would have been on her way to the Johnston’s. Naughty kitten! She was really too comfortable to move. Well, if she were go– What was that? A knock at the door of the shop? but such a curious, surreptitious knock. Patricia knelt where she was and listened. A key dropped to the floor. The sound of the metal on the wood seemed to clang through the stillness. Quiet, then the grating of a key being stealthily turned in the lock. Chills shivered down the girl’s spine, then crawled up again with nerve racking moderation. She could hear the door being cautiously opened. It seemed as though hours passed before she dared lean forward. She could see into the shop. Her heart lost a beat, then plunged madly on. A dim shape knelt before her open safe.

The ruby ring! the thief would find the ring! She must save it. She slipped off her pumps, dropped a blanket over the sleeping kitten and tiptoed to the door. She carefully reached for the blowpipe, jerked the chain, and a foot of flame roared forth.

“Don’t move! Don’t turn! If you do I’ll set you on fire,” she threatened.

Her voice was grim with determination. There was a strangled oath from the man as he glanced nervously at the window and growled:

“Put out that light!”

As Patricia’s vision adjusted itself to the glare she recognized the fur coat and soft hat which he wore. She stifled a sob. The blow-pipe wavered. There came an imperative rapping at the window. Patricia’s eyes followed the sound. She could discern the glitter of brass buttons and a man’s face peering in. She turned the glare of the blow-pipe full towards his eyes. She heard the man at the safe mutter an imprecation, heard him run to the door, heard it bang behind him and swing open again.

The girl’s face was colorless, her heart like a block of ice as she pulled the chain which extinguished the flame and plunged the room in darkness. The rap on the window had become an able bodied bang. She snapped on the bench light and started for the window. On the floor in front of the safe lay the torn half of an envelope into which had been thrust some bills. The girl picked it up and turned it over. She stared down at the address. It was what she had expected:

“Mr. Bruce Mackens–” The rest had been torn away. Patricia thrust the paper into her pocket as the officer thundered again on the glass. She ran to the window and opened it. the rubicund, burly man squeezed himself through and closed it behind him. Patricia attempted a laugh.

“O, but you frightened me,” she protested.

“Sorry, miss,” the officer was gruff but kindly. “My name’s Kelly. I was passin’ by outside when I see a great light bust out sudden in here. Looked like you might hev one of them flame-throwers I see at the movie. The room was dark, an’ I says to myself, ‘There’s sure some trouble in there.’ So I up an climbs the railin’ and tap on the window. But if you’d been dying I couldn’t hev seen nothing with that light in my face.”

“But I wasn’t dying. I make jewelry. I was finishing a piece of work witha blow-pipe and didn’t stop to light up. “

“The Lord save us. You make jewelry. Well, the joke’s on me. You see, lookin’ fer trouble’s my job. I’m after a feller now that I see come out of this home not so very long ago, and–“

“What’s the matter with–” began Mackensie as he appeared at the oopen door. His shoulders were powdered with snow, he had a mammoth bunch of violets in his hand. He stopped in amazement as Patricia flung herself into his arms.

“Why, Bruce dear, when did you return from the west?” she cried feverishly. She hesitated for a fraction of a second before she kissed him. “You’ve been away ages!” Her breath came as though she had been running. “This is Officer Kelly. He saw the light from my blowpipe, thought something might be wrong, and rushed to my assistance. Mr. Kelly, this is Mr. Bruce Mack–“

“Lord save us, he don’t need no introduction, Miss.” Patricia choked back a terrified sob. “Every one at headquarters knows Capt. Bruce Mackensie Cameron, he’s–“

“Cameron!” The word was a whisper. The girl tried to draw away from the man who held her close in one arm. “Not–not the Cameron?”

“Sure, miss. Your feller, Cameron the millionaire, an’ mine’s the same. He’s given more poor devils a chance to start fresh than any man in New York.” The big, burly man grinned affectionately at the younger one. “But as I was telling you when he broke in, there’s a chap who’s been doing a lot to stir up trouble in the factories. We’ve kep’ an eye on him but we’ve let him spiel all he wanted to; better for him to blow off than blow up, but today we was put wise that he was up to some of them Bull–Bull–Sheviky stunts. So I was sent here to get Brown–“

Patricia’s world performed an acrobatic feat or two, then steadied.

“Brown! Are you sure?” Cameron’s voice was curiously shaken.

“Sure! Believe me, headquarters don’t make no mistakes these days. He’s been posing as a painter chap. Has a room here. Perhaps you know him, miss,” with a quick change to his third degree tone.

Cameron answered for her.

“We know him. But couldn’t there be a mistake?”

“There could, but there ain’t! There’s a plain clothes man waiting in his room now. We’ll get him. I must get back. Good night, sir! Good night, miss! Better not use that blowpipe of yours without drawing the shades or lighting up,” he advised as he made a hasty exit.

Patricia nodded dumbly as she closed the door behind him. She dropped to her knees beside the safe. The ring was there. Her money was gone. In its place was a twisted paper. She smoothed it out on her knee.

“Had to take your money. Will pay it back. Leaving in a hurry to make fresh start. Tony.”

Then it had been Tony at the safe. Tony who had taken her money. But the coat and hat? She had seen them on–

“Well?” inquired a tense voice behind her. “Well?”

Patricia sank back on her heels and looked up. Cameron was watching her intently. His face was quite white, the boyishness had disappeared, the veins on his forehead stood out like cords. Her eyes fell before the question in his.

“Do–do you believe it of Tony?” she asked evasively.

He ignored the question. “Why did you greet me as you did when I came in?” he demanded.

She rose hurriedly to her feet. There are some situations one can meet better standing.

“Why–why because I thought that the officer was after you,” with an irrepressible shudder.

“After me!” in incredulous surprise. Comprehension blazed in his eyes. He took one impetuous step forward, then stopped.

“Sit down, little girl, you’re shaking.” He pushed Patricia gently into the chair near the bench and thrust his hands hard into his pockets. “Now tell me everything–everything.”

She looked down at the paper she held and tried to steady her lips.

“I was in the other room in the dark. I heard the shop door open gently. I listened. I thought some one was after the ruby. I stole into the room and turned on the blowpipe. Then I saw a man before the safe, a man in the fur coat and hat I had seen you wear. Then Officer Kelly rapped, the man ran and I found–this, with your name on it.” She drew the torn envelope with its few bills from her pocket and held it out to him.

“T–Tony had warned me that you were deceiving me, and when the officer knocked I thought–I thought–“

“You thought that I had been robbing your safe. Go on,” inexorably.

“I–I thought that if I–I appeared fond of you–he would think that he had made a mistake and–and you could get away. I’m–I’m sorry,” she apologized stiffly. She started to rise.

“As you were!” Cameron commanded with an attempt at laughter. Then she sank back in her seat. “Now I’ll tell my story,” he announced in such a cool, friendly voice that she gave a little sigh of relief.

“When you dismissed me so cavalierly this afternoon, I determined that I should return with my car and take you to the Johnstons. O, yes, I had been invited there, too. I didn’t tell you, there was no time to argue. I had business to attend to, so ‘phoned my man to bring the machine to the florist’s below here. When I reached the place, Brown appeared like an apparition. He was ghastly. He asked if my chauffeur might take him to the doctor’s. Assured me that he would send him directly back. He had neither coat nor hat and he put on mine, which were in the car. He has made his getaway all right. He must have come here first, though. Did you help him, Patricia?” gravely.

“Help him! Why–why I told you I thought it was you. Tony must have been warned that the authorities were on his trail. He supposed that I had gone to the Johnstons and came to borrow my money. He wrote in this note that he meant to make a fresh start. O, don’t you hope he will?”

“I do, indeed!”

There was a mischievous gleam in her eyes, but her lips were tremulous as she looked up at him and whispered with exaggerated humility:

“Please–please, may I make a fresh start? Will you forgive me for think–think–“

With a stifled exclamation Cameron caught her hands and drew her to her feet.

“I am the one who should beg for forgiveness. I should have told you long ago who I was, but I feared if you knew you would send me away. Brown had poisoned your mind. I never took you and Aunt Judith out to dinner, but I feared that some one would recognize me and you would turn me down with that breezily indifferent manner of yours. Aunt Ju knew all about me, but I swore her to secrecy. I should have camped on your trail till you married me to get rid of me–but when I came in a few moments ago–” he flung repression aside and caught her in his arms, “Paddy, do you love me?”

There was furtive laughter in her tender eyes as she looked up at him. A wave of color stained her face.

“Better ask Officer Kelly what he thinks about it,” she evaded tormentingly.

Chastened, spotless, the yellow pendant of his collar gleaming like a bit of crystallized sunshine, Kismet pattered daintily into the room. The white kitten paused abruptly, sat on his haunches, and gazed unblinkingly at the tableau before him. Then with near-human tactfulness he put one fluffy paw before his eyes and uttered a gentle warning:

“Meow!”

which book was this remade into? I have to reread it, but I don’t have time to look for it! Christmas presents are still being made!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hilltops Clear

LikeLike

thank you!!

LikeLike

i really don’t think that telling a woman that she WILL marry you even if you have to kidnap her is the best way to get a “yes” to your proposal. In fact, it isn’t a proposal but an edict. Most women would be turned off by such statements. No woman wants to marry a dictator—but then, they often do.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tone matters. I could imagine that line being said with humor, tacitly acknowledging that the literal meaning would never cross one’s mind. Neither the masterful male nor the simpering female appeals today, but both were popular in former times.

LikeLike