Swift Water is so different from Emilie Loring’s other novels. When Jean Randolph arrives home, Ezry Barker asks,

“Say, Jean, been gittin’ into trouble so soon? Seems though I see th’ old symptoms. Didn’t fetch the Turrible Twin along with ye, did ye?”

But that’s just what this book is about: terrible twins.

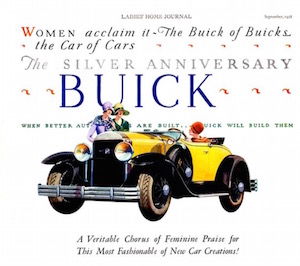

Jean’s mother is an author, so absorbed in her writing career that her marriage has fallen apart, her husband loves another woman, and her daughter lives selfishly, without purpose. Jean enters the story in a dazzling, yellow roadster.

With a wicked, little smile of defiance the girl at the wheel kept on her impetuous course.

Emilie’s characters usually fly planes, ride horses, speak multiple languages, play piano, and sing. But not Jean.

“I have no talent, no parlor tricks. I play the organ creditably, that’s all.”

Secretly, she takes lessons on the church’s carillon, but she shuns church-going itself. She disdains the town girls who attend only to see the handsome minister, Christopher Wynne.

Jean’s father and Christopher Wynne are the book’s conscience–understanding, wise, and compassionate. But neither the father nor the minister is overbearing or dogmatic. That role is left to sanctimonious Luther Calvin.

Salvation stuck out all over him. Having acquired it himself—his brand—he’d bend his energies to converting the world.

Skirmishes for influence in Garston’s religious community dominate the story until a dam bursts, and the town is flooded—a huge flood that carries houses away and sweeps owners from their rooftops. Danger and death force everyone to commit to their beliefs and live—or die—by them, including Jean’s mother, who dies trying to get to her daughter to make amends.

“Jean misunderstood something. I swear that she misunderstood.”

Swift Water was written in 1929, and the timing is important. Emilie usually wrote from September to May and turned in her manuscript before she went to Blue Hill in July. But on May 6th, her brother Robert, her close companion and confidante since childhood, fell to his death from the twelfth floor of a New York hotel—nearly the same date as the death of their mother on May 8th, ten years before.

Did her brother fall to his death, or did he jump? Nearly blinded by illness and gasping for air, he called to the front desk for help, but by the time they got the door open, he lay on the pavement, deep scratches dug into the windowsill, as though he had clawed to remain inside.

Emilie was now the last of her family. Her father, mother, sister, and brother had gone before her. Swift water—unstoppable, inescapable, eternity at its end. She dug deeply for this one, but why? When did she write it? What undercurrents lay beneath the swift waters they navigated before Robert’s death?

Swift Water was published in early November of 1929, just days after Black Tuesday, and it hit a chord. So many were panicked, drowning in debt, disillusioned and desperate, seeking a firm foothold. Swift Water was right where they were. It went almost immediately into a second printing.

Emilie’s sunny personality is her defining characteristic, but in Swift Water, she lays her heart open, lost and questioning. She contemplates her terrible twin in Jean’s mother, who dies without absolution, and recalls the grief of her own mother’s death.

Heart-wringing business this, dismantling a home out of which the occupant had stepped, not knowing that she would never return. Day had followed unreal day–like dull beads on a string which Time relentlessly counted off one by one–as she had sorted and disposed of her mother’s intimate belongings.

Simply and elegantly, she takes on the struggle of souls for guidance and meaning.

Mysteriously restless, she seemed always to be longing for something—she didn’t know what. A purpose in life?

The last thing Emilie Loring would have wanted would have been to be called a “religious writer.” Every time I see her listed that way, I cringe on her behalf. She valued her faith, felt it deeply, and expressed it naturally, but she respected others’ journeys.

The greatest need of the country today is personal religion.

Some called it Destiny, others Force, still others Luck, some called it the Infinite, some called it–God.

Her purpose was, and remained, to entertain.

“My greatest ambition is to tell an absorbing story well. The sort of story which will cause the reader to close the book with a smile, to exclaim: ‘That’s a rattling good story.’”

I didn’t like Swift Water as much as her other books when I first read it. I liked to identify with the girls in the stories, and I kept disapproving of Jean. Why wasn’t she nicer? Thank heaven for Christopher Wynne. He brought all of the romantic tension and fervor and completely showed up bland Harvey Brooke. I wonder at Emilie’s romantic life, that she wrote so compellingly of attraction.

Her pulses responded and set up a clamor. Curious the effect he had had upon her from the moment he had jumped to the running board of her roadster.

An amazing, outleaping force seemed sweeping her toward him. For the fraction of a second she fought a wild impulse to fling herself into his arms. Was she quite mad?

Love is triumphant in Swift Water, but otherwise, Emilie turns things all on their heads. There’s not even her usual reference to Alice in Wonderland, so I will provide one with which to close:

“Dear, dear! How queer everything is to-day! And yesterday things went on just as usual. I wonder if I’ve been changed in the night?” Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Next up, one of my favorites: Lighted Windows

This was not one of my favorites at first, but it’s grown on me. Jean is a different heroine than Emilie’s other heroines, but it was a nice change since we all struggle in different ways. She gets in trouble the minute she enters Garston when she refuses to stop her car because she was speeding. She did not know that the “traffic cop” was actually the minister of the Garston Community Church, Christopher Wynne. Her alter ego, the “terrible twin” continues to get her in trouble throughout the book. She refuses to follow the trail of worshipful female admirers of Christopher Wynne, and her impetuous remarks about religion and ministers are unfortunately repeated to Christopher by his precocious niece, Sally-May.

Jean has come to spend the winter with her father, Hugh and maternal grandmother, the Contessa. Hugh is in love with Christopher’s sister, Constance, but since he is still married to Jean’s mother he cannot marry her, and Jean’s mother won’t give him a divorce. She is a famous author and is afraid it will hurt her with her public. There are actually two villains in this book, Luther “Stone-Faced” Calvin, a religious fanatic, and his “patent-leather” daughter, Sue. And then we have Jean’s admirer, Harvey Brooke, who you can’t help liking despite his tippling. A big part of the plot focuses on the attempts of the Contessa, a retired opera singer, to force Christopher, who has a wonderful singing voice, out of the ministry and into opera.

The part of this book I liked the best is the flood. Jean is in the church when the dam breaks and she is forced to spend the night in the carillon tower, bundled in old coats to keep warm. Christopher is in a cottage by the river, treating the gunshot wound of a man wanted for murder. They are forced by rising water to the second floor and then the roof, where Christopher and policeman Luke Small tie the wounded man and Luke’s invalid wife, Lucy, to the dormer windows for safety. Emilie’s description of the flood is both vivid and heartbreaking.

It’s amazing to me how a book written so long ago remains fresh and relevant today. I feel that about all of Emilie’s books and I’ve re-read most of them numerous times. I will continue to do so!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Emilie did an especially good job with the sexual tension between Jean and Christopher and also with balancing the book’s serious intensity with humor. I’ve always loved the description of her closet’s transformation and wondered if she achieved that sort of modern (for the 20s) dressing room for herself.

LikeLike

I just finished my first reading of Swift Water in several years. You are right that it is so different from the other novels. I appreciate your write up and the connections you make to her life at the time of this book’s publishing. I have never thought of her as a religious writer. She’s mostly expressed a general protestant religion ethos than say, the Episcopal or Presbyterian religion. She was more about a generally expressed faith in the Christian God. Perhaps in this book, where the various congregations combined, EL sets out her views on organized Christianity.

Whatever EL thought of religion, she certainly put on pen and paper clearly what she believed are ways of right living. I wonder what she’d make of today’s society. Her frequent statements about marriage and divorce, for example, and their effects on individuals and society have been shown to be prescient. A a child of divorce, I share her views.

There is so much to attempt to delve into regarding this book. Faith, the heroine is fighting so much. This is an intensely personal and spiritual battle of Faith’s we follow. I wonder how much of Faith’s battles that EL experienced as she grew up. She wrote after she was about 50, so she knew who she was and what she believed by then.

Faith is caught between the values of her mother and her father, and between her love for both of them. She’s defiant about resisting faith in God. She can’t possibly be good enough for the minister as a child of a failed marriage. And the minister of course does not fit expectations of a stuffy rigid person. (Luther Calvin is though; and he was named after both Reformation leaders of protestantism.) Christopher Wynne is a real “flesh and blood” or “honest to goodness” (going on memory) lover. He’s no mealy mouthed fellow. He’s a man of feeling, passion and conviction. Jean had to come to realizations about herself and what she believed before she could allow herself to love Christopher.

This book is interesting because I did my searching also. EL was a helpful guide in my youth. We all have our search in life. This book could be of interest to a wider audience for the self-searching inside as well as the usual EL features and writing we appreciate.

LikeLiked by 2 people

What a thorough review! I used to think this book arose from Emilie’s grief at the loss of her brother, but she completed the manuscript several months BEFORE his death. Her views on religion stayed pretty close to her Universalist upbringing, I think, but her attitudes toward both drinking and divorce underwent change over the years, becoming more nuanced, less rule-bound. I agree that it’s a good one for times of searching–which all of us have!

LikeLike

Ah, a Universalist upbringing makes sense from my reading of EL. It’s clear that faith is important to her characters, but it’s never been more specific than a Christian faith. I wondered if she had lightened up a bit on drinking and divorce. Things don’t always work out. It’s just how life goes. And not all drinking is evil. Not all who drink get drunk.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just realized I called the heroine “Faith”! Faith Randolph is in Look to the Stars. Her parents were divided as well. That one worked out more happily. In this story it is JEAN Randolph. Faith as a concept is the subject of the book!

Cheers!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on tempehighschoolclassof1971.

LikeLike